“Father, my only purpose in life is to complete your work.”

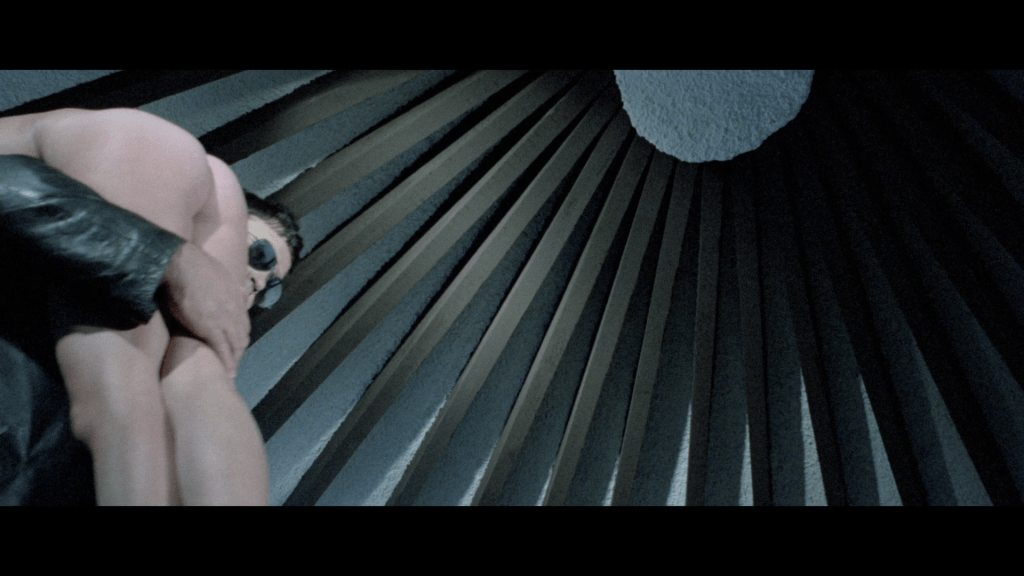

“Given that so much of the appeal of The Awful Dr. Orlof depended on Gothic style and atmosphere, Franco was taking quite a risk by restaging the story in the present day with prosaic mise-en-scène. Sadly, a few nice compositions and locations here and there do not adequately compensate for the lack of baroque and chiaroscuro delights.”

— Stephen Thrower, Flowers of Perversion

“Franco used the name Orloff several times throughout his long career, more often to please the producers than out of genuine personal need. So much so that he frequently twisted Orloff’s identity, as if to distance himself from it.”

— Francesco Cesari & Roberto Curti, “Reflections on Orloff”

The closest thing to Spanish director Jess Franco’s Son of Frankenstein, the alternate title could very well be Son of Orloff. The Never Stop Filming Jess Franco train continues down the tracks during his 1980s Golden Films Intl. era, when he had creative freedom, a camera, and a core group of actors willing to do whatever he asked in exchange for an all expense paid trip to Costa Blanca, Spain. The story goes that he told best bud and man of many hats, Antonio Mayans (to paraphrase): “We’ve got Howard Vernon, let’s do another Orloff.”

Jess Franco had made many Orloff and Orloff-adjacent mad scientist face transplant films in the interim between 1962’s original, landmark Spanish horror film, The Awful Dr. Orloff, but none that ever felt like a real continuation of that story. Enter The Sinister Dr. Orloff (not to be confused with The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff), both a bold, sunkissed re-imagining of the Orloff story and a bloodline extension of it. But whereas the The Awful Dr. Orloff had the briefest of nudity in an exposed breast, The Sinister Dr. is allowed to bare full bottom.

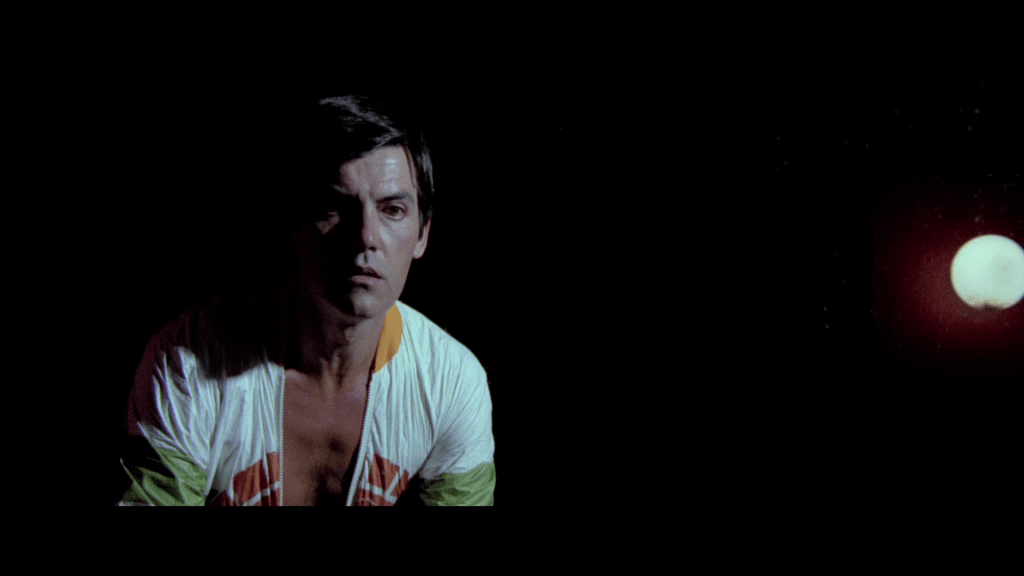

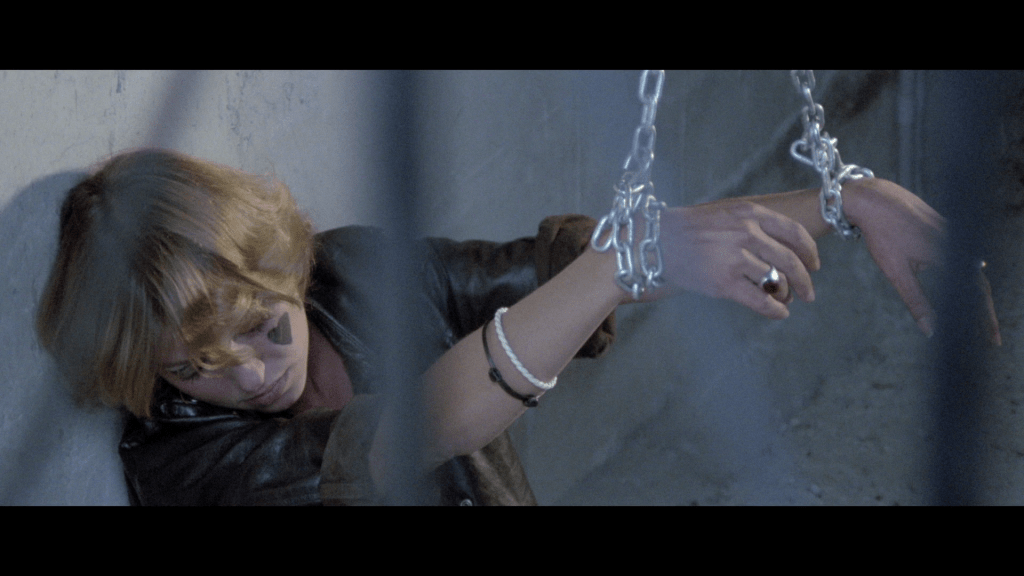

The 1962 version existed in a sort of nebulous Victorian age of horse and buggies, so it’s best not to think too hard about the timeline, but based on the clues, we’re led to believe Vernon is playing the same mad doctor—now aged, in a wheelchair, with a shock of white hair reaching for the sky; “hidden behind a glass panel in his lab, like a gloomy ghost,” according to Cesari/Curti. Antonio Mayans plays his son, Alfred, who against his father’s wishes, continues with his experiments to metaphysically transfer the soul of their comatose mother, Melisa, into the body of a sexy young thing. It’s absolutely Oedipal, as Alfred’s final victim, just like in The Awful Dr. Orlof, is played by the same actress lying on the slab (in this case, Rocío Freixas).

To find a proper mommy proxy, Alfred prowls the streets of downtown Alicante, a place Franco loved because of its otherworldly aura as both stuck-in-time fishing village and burgeoning tourist destination. By the 80s it was now almost completely unrecognizable from its roots, the one-story boarding houses bulldozed to erect multi-level beachfront hotels. Alicante was also home to Franco friend and architect, Ricardo Bofill’s striking La Manzanera complex, which provided a cheap, future-mod shooting location. But it’s the cinema verité style run-and-gun street photography that really stands out, with Mayans noting that instead of using fancy filters Franco pushed the limits of the Kodak film stock during processing to achieve the eye-popping colors of the city lights and neon marquees.

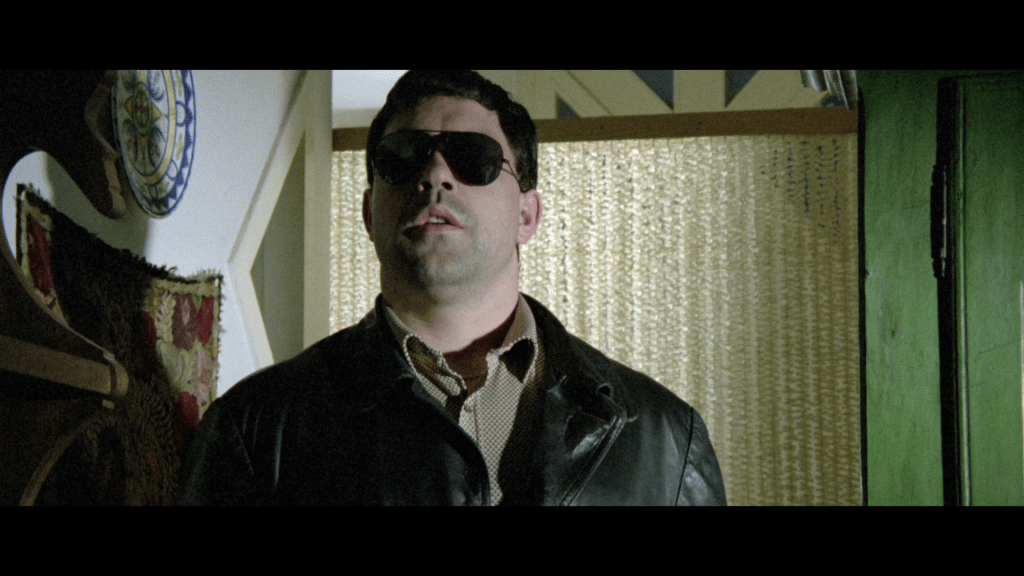

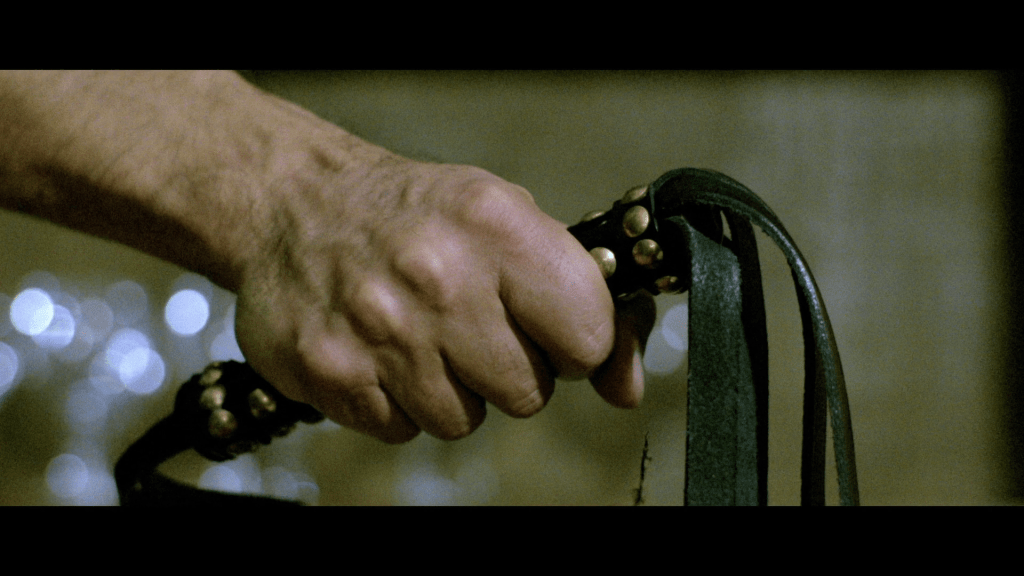

That said, some of it gets a little repetitive, with the same series of prostitute kidnappings, the same staircase where the leather jacket and aviator shades blind automaton, Andros, carries the victims, the same Prophet-5 keyboard musical cues. But to add a new layer to the plot, elder Orloff now regrets his past life of crime, but does nothing to stop his son from his unholy, metaphysical experiments (flashing lights, sci-fi levers, a woman tied to a red velvet gurney, disintegrated bodies).

There could have been an interesting conflict between the wizened father and his upstart young son who harbors incestuous feelings towards his mother, the elder doctor’s late wife, but Franco never goes there, except for one confusingly edited scene at the end, where it appears as if Vernon’s Orloff has been playing 3-D chess this entire time, getting rid of all his adversaries and potential rivals with one twist of the canary yellow knob. Or he’s just a laughing maniac.

For fans of Franco’s Orloff Mythos, it’s absolutely worth a watch. I don’t agree with Stephen Thrower that El siniestro doctor Orloff is “marginally better than the talky and tedious Los ojos del doctor Orloff (1973).” I’d put them on about equal footing; they are very different movies, and I really do appreciate the 70s mood of the latter. What I agree with is that it’s a treat to see Howard Vernon “back in the role that made him a horror icon,” and that neither film can “hold a guttering candle to the Orloff films of the 1960s.” If nothing else, it’s fun to watch Franco recreate the classic Orloff under the less restrictive censorship laws of the 1980s. You can’t argue that this is anything but primo Franco: una camera y libertad.

Thanks to McBastard’s Mausoleum for the images. The Sinister dr. orloff is now available from mondo macabro