“A wild, heedless love, bordering on heroism.”

Then I saw that there was a way to hell, even from the gate of heaven, as well as from the City of Destruction. So I awoke, and behold it was a dream.

— John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

I had in my heart goals of creating something like a cross between von Sternberg and George Cukor, sort of drag queen-like performances, which I would then, since I’m Icelandic Canadian, tamp down into a Scandinavian coolness, so that my drag queens would be less disinhibited and more straight-faced. But these queens would be there in spirit, their disasters exploding at the seams of the plot. Repressed hot messes!

— Guy Maddin, “Double Exposure“

Dispatched by Wounds Innumerable

In his landmark study of World War I trench warfare, The Great War and Modern Memory, author Paul Fussell introduces his fourth chapter, “Myth, Ritual, and Romance” with a vexing inquiry: “That such a myth-ridden world could take shape in the midst of a war representing a triumph of modern industrialism, materialism, and mechanism is an anomaly worth considering. The result of inexpressible terror long and inexplicably endured is not merely what Northrop Fry would call ‘displaced’ Christianity. The result is also a plethora of very un-modern superstitions, talismans, wonders, miracles, relics, legends, and rumors.”

One of those myths was that of “The Crucified Canadian.” From Fussell: “The usual version relates that the Germans captured a Canadian soldier and in full view of his mates exhibited him in the open spread-eagled on a cross, his hands and feet pierced by bayonets. He is said to have died slowly.” Rumors of ghostly figures were also common: “One of the best of these, bred by anxiety as well as by the need to find a simple cause for the failure of British attacks, is the legend of the ghostly German officer-spy who appears in the British trenches just before an attack. He is most frequently depicted as a major. No one sees him come or go. He is never captured, although no one ever sees him return to the German lines. The mystery is never solved.”

In his poem, “Recalling War,” Robert Graves writes of the feeling of erotic elation at the onset of the Great War. “For Death was young again,” he writes, and he and the lads were thrilled by the idea of “healthy dying, premature fate-spasm.” This readiness to die cumming is part of a wider, well-trodden association of war and sex, which Fussell elaborates upon: “given the deprivation and loneliness and alienation characteristic of the soldier’s experience—given, that is, his need for affection in a largely womanless world—we will not be surprised to find both the actuality and the recall of front-line experience replete with what we can call the homoerotic.”

Male love during wartime is further venerated by the usually cynical novelist Thomas Pynchon, writing in Gravity’s Rainbow: “In the trenches of the First World War, English men came to love one another decently, without shame or make believe, under the easy likelihoods of their sudden deaths, and to find in the faces of other young men evidence of otherworldly visits, some poor hope that may have helped redeem even mud, shit, the decaying pieces of human meat….While Europe died meanly in its own wastes, men loved.”

All this to say, in Archangel: A Tragedy of the Great War, Canadian director Guy Maddin was simply continuing a long tradition of fusing war with the macabre, the surreal and the strangely arousing, despite, like I said in my last review, his script being “inspired more by the folklore and propaganda of the Great War than the facts of that very real port of entry town of Arkhangelsk.” Maddin’s trenches are small villages unto themselves (one night, beset by mysterious white rabbits, “fluffy harbingers of death”). His ghosts guide soldiers out of danger, not into it. And the amnesiac soldiers of Maddin’s film are fighting over a female cipher, when they should be holding each other. But both Fussell’s book and Maddin’s amnesia melodrama share an obsession with things remembered through a haze of half-truths, horny scribblings and the myths we tell ourselves (“total forgetfulness”) just to survive another day on the front line.

Oh, to be a lustful youth in the trenches! Or safer yet, to play one in a Guy Maddin film.

The Transfer:

The new Kino Lorber blu-ray release and 4k scanned restoration is a full six minutes shorter than the 2002 Zeitgeist Films DVD release. Like Tales from Gimli Hospital, this appears to be more of a “redux” restoration than straight scan and color correction, with Maddin seemingly making some snips and edits here and there. Either way, it’s a major upgrade. You can really see the edges of the warehouse sets in this crisp, new transfer. Maddin also fixed the blue and red-tinting applied to the “Sleepy Trenches” segment to better match the B&W look of the rest of the film.

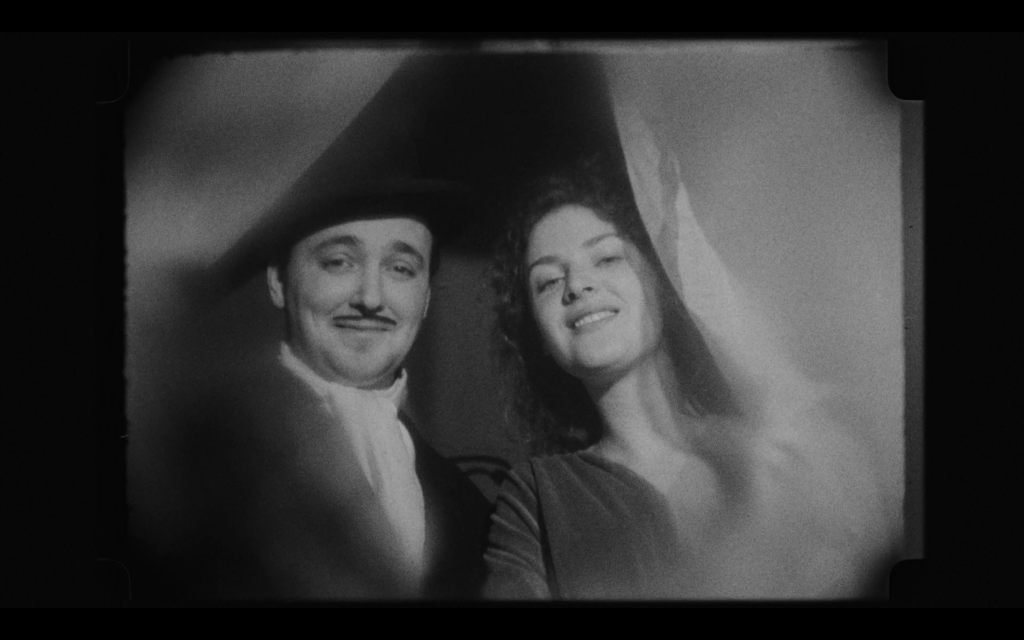

the new 4k restoration of Archangel can be purchased through kino lorber . thanks to filmswelike for the images