Before he worked alongside Henry Fonda in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, before he got steamy in erotic auteur Radley Metzger’s The Lickerish Quartet, before he watched giallo queen Nieves Navarro erotically eat oily fish in Luciano Ercoli’s Death Walks on High Heels, and before he starred in Sergio Corbucci’s Euro Western masterpiece, The Great Silence (chewing up scenery next to Klaus Kinski, one of cinema’s great scenery chewers), American actor Frank Wolff was getting his feet wet in a quadrilogy of films for influential, zero-budget movie maker, Roger Corman.

- The Wasp Woman (1959, dir. Roger Corman)

- Beast from Haunted Cave (1959, dir. Monte Hellman)

- Ski Troop Attack (1960, dir. Roger Corman)

- Atlas (1961, dir. Roger Corman)

Wolff got a late start in the business, making his film debut as a henchman in Jack Sher’s The Wild and the Innocent at the age of 31. Besides being a chameleonic actor that could play almost any role, one of Wolff’s greatest assets was that he appeared perpetually middle-aged, with an expressive and lived-in face that eventually made him a beloved and bankable character actor during Italy’s boom period of the 1960s and 70s.

What makes Wolff’s story unique is that he had only a handful of credits to his name before he made the leap to Europe, a move reportedly encouraged by collaborator Roger Corman. Italy and Spain were known for employing American talent to add name value to their marquees. The actors were paid well and ate good, but more often than not, working in European genre cinema was still seen as a form of debasement for a Hollywood movie star, saying nothing of an up-and-comer like Wolff.

For every Clint Eastwood, who found superstardom across the pond and came home a conquering hero, there was a Carroll Baker, whose move to Italy and subsequent roles in a series of “nudity required” thrillers for director Umberto Lenzi, was proof to her Hollywood detractors that she was a has-been.

Not only was Europe a haven for those that couldn’t cut it in Hollywood (and there were many), it was also a place where longtime supporting actors could find work in a leading role, with their name in the biggest font at the top of the poster, unrestrained by the often stifling, political atmosphere of Tinseltown.

The Demon (1963), The Lickerish Quartet (1970), Death Walks on High Heels (1971), Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

For many actors, they had no choice. The post-World War 2 Hollywood blacklist of anyone that held sympathies for, let alone a card carrying membership in, the Communist party, meant that Europe was the only option if they wanted to continue making a living in film (I’m thinking specifically of Lee J. Cobb and many of his friends).

Frank Wolff’s story is different. He didn’t leave Hollywood with his tail tucked between his legs. He wasn’t a major star looking for greener pastures, and he wasn’t fleeing political persecution. He left America of his own accord with nothing but his talent and his face. He barely even had a name, and only a handful of low-budget film credits on his resume. In many ways, Frank Wolff willfully abandoned Hollywood before Hollywood could abandon him.

I turned out alright for him. Wolff would end up working with some of the most exciting and influential directors in 1960s/70s European cinema, starring or co-starring in some of the most beloved films from the era, many of which are still undergoing restoration, reevaluation and finding a new audience with young viewers looking for unique faces, wild stories, intense action and the kind of cosmopolitan visuals you don’t find in modern cinema.

But before all that, Wolff acted as a protege of sorts to producer, director, jack-of-all-trades, Roger Corman. Wolff hooked up with Roger and his brother Gene at the perfect time, just as they were setting up their own production company, The Filmgroup, which was an opportunity for the Corman brothers to own, distribute—and beneficial to Wolff—cast their own movies. It also helped that they didn’t have to split costs with American International Pictures (AIP).

— First Delivery Man (Frank Wolff), The Wasp Woman

Frank Wolff’s first part in a Corman picture was in The Wasp Woman, a late 1950s b-horror take on the classic “woman in business” film from the 30s. In it, Janice Starlin (Susan Cabot) attempts to save her business, and her pride, by injecting herself with an experimental enzyme extract from royal wasp jelly. To terrifying results.

Wolff appears at the 44 minute mark, playing a small but memorable role as a wise-cracking delivery man with a toothpick between his teeth who hits on the “pretty puss,” nail-filing Starlin Cosmetics secretary. His scene is inconsequential, but adds a bit of light comedy to the film. Clearly Corman saw something in him, enough to give him a few lines to warrant his name being listed in the opening credits.

His next role would be more substantial, and a minor breakthrough.

— Alexander Ward (Frank Wolff), Beast from Haunted Cave

Beast from Haunted Cave was filmed by Monte Hellman, a close friend of Wolff from their days at UCLA (where Wolff won Best Acting awards for the lead in Macbeth and The Lower Depths). Wolff plays the leader of a Chicago-based gang of robbers who blow up a mine in the Black Hills of South Dakota as a distraction for a gold bar bank heist. Unbeknownst to them, the bombing awakens a wispy monster that tracks them to the remote backwoods where it terrorizes the most arrogant and sinful of the bunch.

Wolff was only 30 when the film was shot, and despite already naturally appearing like a wizened veteran, he has sandy gray makeup added to his hair and mustache to appear even older. The film was shot around an actual abandoned mine in Deadwood and the still-operating Terry Peak Ski Area in Lead, South Dakota. Corman was eager to escape LA’s Bronson Canyon and Griffith Park, to do something different, something with a whole new look (of course, there were also monetary incentives).

Besides the scenery, Wolff is the film’s centerpiece, giving a naturalistic performance as Alex Ward, a small-time boss trying to hold his crew, and his love life, together. Playing Ward’s ride-or-die dame, the gangster’s moll, is Sheila Noonan in the role of “Gypsy,” an alcoholic, world-weary woman who has eyes for the local ski instructor (Michael Forest). It’s her attraction and openness with Gil (Forest) that sets the crew up for failure.

It doesn’t help that Gil is not as simple and carefree as he seems. Early in the film he correctly identifies Gypsy as “a faded woman regretting a misspent life.” In Gil, she sees an escape from her life of crime, and more importantly, the abusive Ward. After the bank heist, Gil is hired to lead the gang on a cross country, multi-day ski trip to a remote cabin where they plan to hole up for a few days while the mine bombing and robbery blow over. It’s in the remote backcountry where tensions boil over, and Ward’s violent threats (“some day I’m going to shut that pretty little mouth of yours for good.”) become physical when an inebriated Gypsy openly kisses Gil on the mouth.

The relationship between Ward and Gypsy is the crux of the film, and is what makes it more fascinating than your run of the mill papier-mâché monster film. Gypsy is given an unusually complex backstory. In one scene, she opens up to to Gil, admitting that she enjoyed Ward’s rough ways early on in their relationship, when she was an “underpaid model at a wholesale house,” and he was the “young and loaded” man that gave her the material things she craved, that only a life of crime could provide. In other words, the giant wingless hangingfly hunting them across the Black Hills is actually the least of this group’s problems.

Charles B. Griffith, the screenwriter for Beast from Haunted Cave, claimed that later in his life, Wolff told him it was his favorite of all the pictures he had made in his career. This is, objectively, ridiculous, but I don’t doubt that Wolff said it. It’s clear that working with close friend Hellman, and early mentor, Corman, meant a lot to him as a developing actor. In his darkest moments, I imagine it was a time in his life that he could look back fondly on.

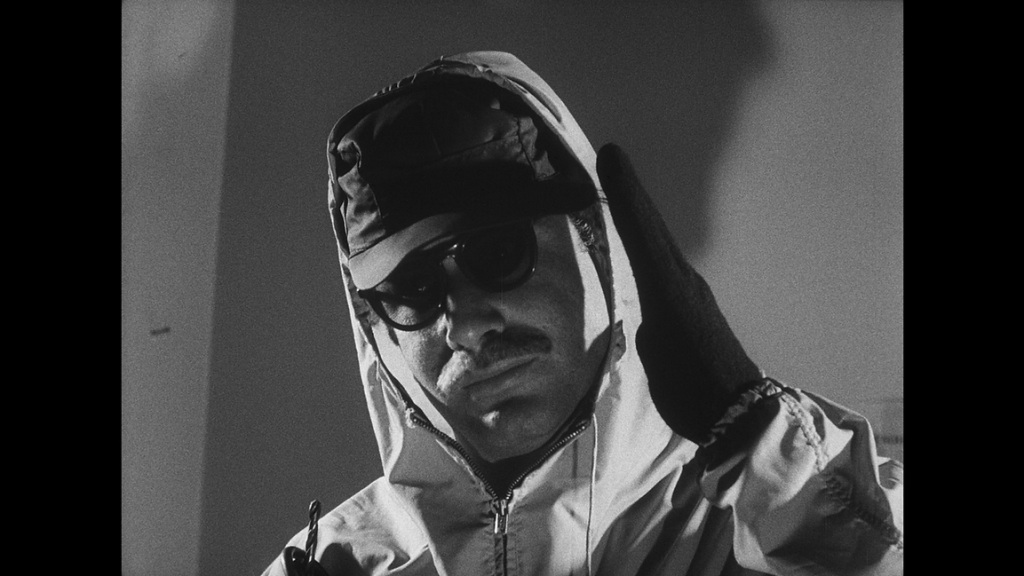

— Sgt. Potter (Frank Wolff), Ski Troop Attack

Following Beast from Haunted Cave, Roger Corman decided one feature-length film was not enough, and to make the most of the expense of traveling to South Dakota, he decided to shoot a serious, isolated war drama using many of the same locations, cast and crew. By now, Wolff and Haunted Cave co-star Michael Forest must have felt like pros on the snow sticks, which would work to their advantage, as Ski Troop Attack features a lot more cross-country maneuvering.

Author and screenwriter C. Courtney Joyner calls Ski Troop Attack “a somber World War 2 action film.” The film was planned around stock footage of tanks and soldiers that Corman had purchased, but in the end, those grainy scenes were only minimally used. Corman rightfully realized it wasn’t really needed after he saw the actual Black Hills footage he was able to capture as stand-in for Hürtgen Forest, Germany, 1944.

Roger was asking a lot of his crew under the conditions. The five week shoot for both Beast from Haunted Cave and Ski Troop Attack was not easy, with the anticipated February/March snow made even more difficult with the addition of a broken leg on an uncredited extra and a minor avalanche that disrupted the virgin white scenery Corman craved.

There are numerous scenes, especially in Ski Troop, where the cast, aided by the local Lead and Deadwood ski teams, are trudging up difficult terrain, crawling through deep snowdrifts, climbing bridge supports, and generally, putting their bodies on the line for a crazy production that only decided to shoot in the area because of the financial incentives offered by the South Dakota Chamber of Commerce and the cheap price of a non-Union Chicago film crew.

Visually, the end result is astounding, but like Beast from Haunted Cave, this is a character-driven adventure film. Frank Wolff plays a trigger-happy, kraut-killing sergeant under the leadership of Michael Forest’s higher-ranked lieutenant. It’s American ground infantry vs. German Panzer Division; but it’s also Sergeant Potter (Wolff) vs. Lieutenant Factor (Forest), the two men butting heads on decision making but never coming fully to blows. In a twist on the usual formula, the film never truly delivers on the tension between the two men, instead, it focuses on how the elite unit must learn to work together to infiltrate behind enemy lines and destroy a key bridge used for German troop movements.

Instead of Sergeant Potter leading a revolt against Lieutenant Factor, and getting killed in the process, the two men end up as the only survivors of the bloody finale, skiing off into the Germany-via-South Dakota sunset, a pile of white snow suited dead bodies in their wake. The final word from Factor to Potter:

“Well sergeant, did you get enough fighting?”

— Proximates the Tyrant (Frank Wolff), Atlas

The last project Wolff did with Roger Corman was Atlas, a sword and sandal wannabe-epic shot on location in Greece. It was, to put it lightly, a troubled production, but it once again reunited Wolff with Haunted Cave and Ski Troop co-star, Michael Forest. Wolff plays Proximates the Tyrant, looking the youngest of his career with shorn mustache, clean shaven face, and mop of curls. Forest is the titular Greek wrestler, Atlas, who catches the eye of Candia (Barboura Morris), which infuriates the quietly jealous Tyrant. The Tyrant enlists Atlas to help him fight the enemy-state Thenis in a case of keeping your friends close and your enemies closer.

Maybe it’s the loose robes, the smooth face, or the Greek setting, but there’s a delightful air of effeminacy to Wolff’s character. The pitched battle scenes are awkwardly staged, but there’s a lot of fun in watching Wolff call out spear and shield formations and act as inspirational leader to his men. And for all the film’s low-budget problems, it’s a treat for Wolff fans to see him in such a histrionic role, surely a chance for him to channel his UCLA theater glory days.

The film loses a lot of steam in the second half, with a long, phony trial sequence, but it reaches a nice crescendo of madness after Proximates loses both his best girl and his greatest fighter. It’s in this last 20 minutes where Wolff really gets to let loose as Proximates finally unravels: screaming at underlings, stabbing traitors, and making a doomed last stand. Proximates is the villain, but thanks to Wolff’s charismatic portrayal, you hate to see his ignoble end.

Frank Wolff wouldn’t return to the States after the Atlas production wrapped. Instead, he boot-hopped to Italy, just a year later co-starring in Francesco Rosi’s Italo-realist crime drama, Salvatore Giuliano. Wolff’s successful role in that film as Gaspare Pisciotta quickly earned him a place at the Italian table, and from that point on he would work nearly non-stop in this adopted country until his death.

At the same time Wolff was making Euro westerns in Spain and Italy, old friend Monte Hellman was being feted in Hollywood for his acid westerns and gritty road movies. It’s hard not to wonder what might have happened if Wolff had returned to Hollywood, maybe even linking up with Hellman again, maybe even playing the role in The Shooting that went to Warren Oates.

There are a lot of “what ifs?” in Frank Wolff’s career. But what we do know is that fellow actors and friends all had high praise for him as a person and as a professional. Those who knew him well said he always had a smile on his face, but was prone to bouts of depression. That malaise worsened after a messy divorce, and with movie roles drying up, Frank Wolff, tired and despondent, aged 44, slashed his throat with a straight razor in a small apartment he occupied next to a Rome hotel room. It’s a sad end to the life and career of a man who had already done so much, but in many ways, was just getting started.

thanks to ian jane for many of the Corman screen captures. you can purchase the beast from haunted cave/ski troop attack blu-ray double feature from film masters

Works Referenced:

Beast from Haunted Cave commentary track, C. Courtney Joyner and Howard S. Berger, Film Masters, 2023

“Corman Goes to War,” C. Courtney Joyner, Film Masters LLC, 2023

Frank Wolff, Biography, Internet Movie Database

“Frank Wolff Dies; Screen Actor, 43,” The New York Times

“Little Shop of Genres: An interview with Charles B. Griffith,” Senses of Cinema

Ski Troop Attack commentary track, Tom Weaver and Larry Blamire, Film Masters, 2023