“Maybe it’s my fault. Maybe I want all these things to happen, like a curse.”

“It’s one of Franco’s most outstanding erotic dramas and deserves to be thought of as a kind of palimpsest for the other sex films, be they frivolous, sleazy or disturbing. Franco, as always, is fascinated by beautiful women, especially beautiful women in live sex shows—here, though, his voyeurism takes account of the possibility that the girls cavorting onstage for the enjoyment of punters may be nursing terrible feelings of ennui, disappointment and betrayal.”

— Stephen Thrower, Murderous Passions

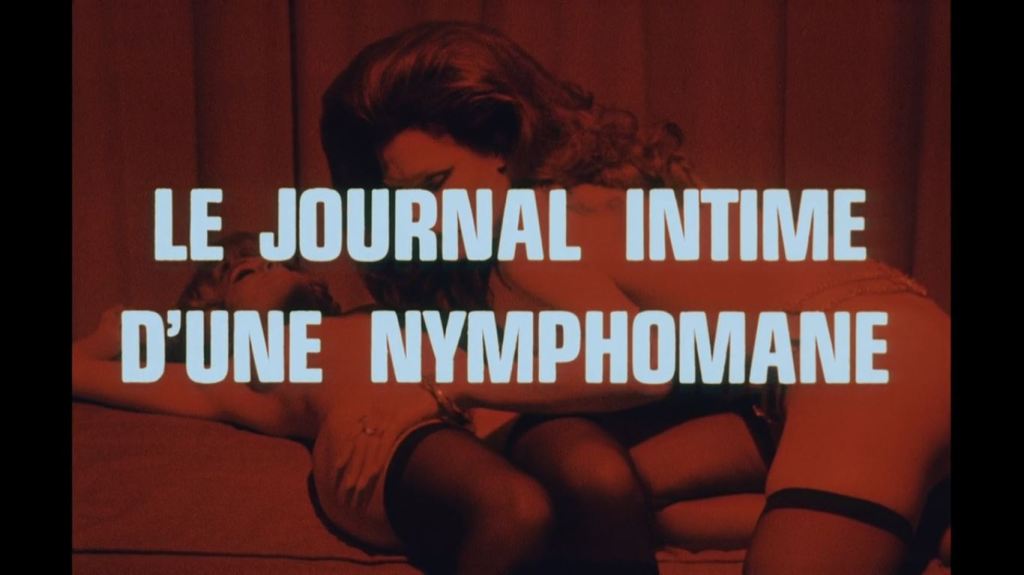

Burn After Reading: The Dehumanization of Linda or, Linda and Her Week of Wonders. In the boldly titled Sinner: The Secret Diary of a Nymphomaniac, European cult director Jess Franco engages Hypnosis Mode, cobbling together his own disparate footage, taking liberties with a plot seemingly created in the post-production editing bay, and layering a wild mashup of prog and acid-rock on top of it all to create a narcotic, Sadean-noir sludge. It shouldn’t work, but it does. A recurring motif of the World of Franco.

Franco is still in his post-Soledad Miranda phase, crying into his absinthe over her premature death, searching for a replacement muse, and Spanish beauty Montserrat Prous briefly appeared to be a willing, temporary participant for the two years they collaborated. Prous, dark-haired, with an innocent face, acted in only a handful of Spanish and Italian films in the 60s and 70s. Under Franco’s direction, she could do the naked bed writhing as well as Miranda, but never reached the hedonistic, mouth-agape-to-heaven level of orgasmic transcendence the eventual winner of Jess Franco’s affections, long-term partner and wife, Lina Romay. In fact, based on an illuminating interview1 that Prous gave in 2014, it was the arrival of Romay that caused her to drift away from Franco’s inner-circle: “They started shooting porn and I didn’t want to be a porn star.”

As a stand-in for the Marquis De Sade’s character of Justine, though, Prous is fantastic as Linda Vargas2, the woman at the center of the story, the Charles Foster Kane of this largely told-in-flashback erotic drama. The difference being that the mystery at the center of Sinner is not a man’s dying words, but the throat-slitting actions of a mentally broken working girl. Prous, with a slender frame and a more virtuous face than either of the aforementioned Franco Girls3.

But unlike Franco’s many inspired-by-Justine adaptations, the gaze of Sinner doesn’t linger on Linda’s downfall, it doesn’t relish in the suffering, but instead gives a more sympathetic view of what film critic Stephen Thrower calls “a slide from innocent naivety to bitterness, and then further, into addiction and self destruction.”

The film opens with a red light, rising rage sex show from throbbing, acid rock hell, until it very briefly becomes an Inspector Jess murder mystery. An easily excited, champagne-plied John is incriminated in a suicide/murder plot, but in a giallo-like twist, the man’s prudish, uptight wife, Rosa (Jacqueline Laurent), ends up doing the bulk of the investigating. Rosa (or “Ruth” in the English language version) doesn’t believe her husband is a murderer, but she doesn’t think he’s completely innocent, either.

In her questioning of the women involved with Linda’s past life, Rosa uncovers the mystery around the girl’s journey into perversion, and eventually, gets ahold of the titular diary itself. In doing so, and through the personal recollections from one of Linda’s closest friends, a Countess played by Anne Libert, Rosa tastes a bit of that forbidden fruit herself, and is irrevocably changed.

What reads like a standard exploitation story of a good girl turned bad, Franco destructs with his nightmarish story layering. There are flashbacks within flashbacks, many of which bleed into the present—a scene from the retold past will zoom in and trail off, only to then zoom back out, no cuts, and we find ourselves back in the original room with Rosa, who is the listener of the story. I don’t know how to describe it, it’s almost like a faux-match cut. I’ve never seen it done before, but it’s another one of the many cost-cutting Franco maneuvers that ends up being brilliant and experimental in its simplicity.

That said, it’s still up for debate how much of this experimentalism comes from Franco himself, and how much from Gérard Kikoïne, his silent partner/editor at this time. Kikoïne was often given the footage, a loose script, and instructions to patch it all together. It may seem like a maddening way to work, and calls into question what a “Franco film” really is, but the idea of the editor as one of the key authors in a movie’s creation is not an outlandish concept. There’s also the issue of different language options, which adds further complexity to the question of authorship and definitive versions.4

The players in this dark morality tale are uniformly fantastic: Anne Libert gets an introduction as a mysterious countess under big shades that echo Miranda on the veranda from Vampyros Lesbos. The exotic Kali Hansa gets the “fun girl” role, a dancer and model who introduces both Linda and Rosa to the joys of feminine touch. Jacqueline Laurent gives a surprisingly sad performance as the wifely Rosa, a sexually conservative woman who has her eyes opened to both the pain and wonders of the world. My one qualm is that I found her journey’s end too ambiguous—after securing the diary and paying respects to Linda’s cold body on a slab, she chooses to throw the book in the ocean instead of bringing it to the police.

It seems as if there is no justice for Linda, and even Rosa, when confronted with the truth about her husband, and after experiencing her own sexual awakening, appears to remain blind and unpleasured. Critic Tim Lucas, in his recent commentary on the film, shared similar ambiguity regarding the ending, noting that while Ruth sides with Linda by throwing the incriminating journal (which would clear her husband of murder) into the ocean, it’s not immediately clear if the act is out of “spite or sisterhood.”

The most vile character is saved for Europe’s hardest working actor, Howard Vernon, portraying a progressive “doctor” who listens to tortured Linda pour out her trauma and fall into his arms, only to emotionlessly prescribe her two sedative pills and sleep. After his clinical treatment fails, some months later he spies Linda walking the city streets with a man. He sexually assaults her in a fit of rage, taking her body in exchange for medical services rendered. It’s the film’s climactic moment, the emotional knife to Linda’s throat. Vernon’s head bobbing in and out of the frame, with Linda’s catatonic face in the center, is one of the most chilling in all of Franco’s many, many images.

In this moment, Linda’s trust is broken, and her once idealistic idea of sex as a form of freedom, as a form of martyrdom even, is crushed completely. There’s no other option but to give her life death in the service of revenge. What Linda didn’t expect, is that her final, self-destructive act would begin a new story, that of Ruth’s own deliverance from sexual repression. Sinner, therefore, is actually the story of her liberation.

“Is it turning you on or off?”

“Both, perhaps.”

“In pornography, a so-called nymphomaniac is simply a male fantasy construct, a woman who’s ‘begging for it’ and willing to spread her legs for even the tawdriest of ‘dates.’ In Sinner, however, the implications are darker. Here, a nymphomaniac is a woman whose appetite for sex has curdled into obsession and self-destructiveness.”

— Stephen Thrower, Murderous Passions

Footnotes:

- The interview also includes one of my favorite anecdotes about Romay. Actress Kali Hansa told Prous that she didn’t like to shoot with Romay, who she found unprofessional in sex scenes “because she gets horny.” ↩︎

- One of the many Orson Wells references in the film, the surname of Vargas is an important one in Touch of Evil ↩︎

- Prous’ closest companion in the Francoverse would be Susan Hemingway, who goes through similar, habit-forming misfortunes in Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun ↩︎

- I have watched the film with both available audio tracks, English, and French with subtitles. I’m not sure which I prefer. The English track has “punchier” audio, and it sometimes appears that Prous’ lips match the overdubbed dialogue. But on the other hand, the sound of the French language, in my opinion, pairs better with the subject matter. The subtitles for the French audio are more “flowery,” and have the effect of making some of the more sordid sections of the diary sound less like Penthouse-letters. For example: the English audio of “They hurt her when they penetrated her” becomes “She was hurt each time a man entered her” in the French v.ersion. ↩︎

The blu-ray of Sinner: The Secret Diary of a Nymphomaniac can be purchased through Kino Lorber