“What is this realm of soft shadows and silence?”

The word that could best describe this feeling

Would be haunted

I touch the clothes you left behind

That still retain your shape and lines

Still haunted

— Love and Rockets, “Haunted When the Minutes Drag”

As someone who frequently writes about movies, I’m often asked what my favorite movie is. My stock response for the past few years has been “A Virgin Among the Living Dead,” not only because A Virgin Among the Living Dead is my favorite movie, but because I think it’s funny to say my favorite movie is the horrendously titled A Virgin Among the Living Dead.

But it wasn’t always titled A Virgin Among the Living Dead. Like many European exploitation films from the 1970s, prolific Spanish director Jess Franco’s macabre masterpiece was given different titles for different markets and almost endlessly tinkered with in post-production to capitalize on contemporary trends. In the 70s, that trend was the erotic, so producer/writer Pierre Quérut shot and inserted five minutes of additional footage featuring Alice Arno presiding over a florid orgy. The film was retitled Christina, Princess of Eroticism.

During the 1980s VHS boom, the film found new success after Jean Rollin, French director of the fantastique, was commissioned to shoot even more incongruous scenes for the film, this time of the shambling undead, an obvious cash-in on the zombie craze that gripped European audiences after the release of George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, and it’s re-edit by Dario Argento under the title Zombi.

This new version of Franco’s film reverted back to its A Virgin Among the Living Dead title, was given a beautifully grotesque one-sheet, and thanks to French production company Eurociné—adept marketers of cheap shlock, keenly aware that an eye-catching title and lurid box art was all that was needed to make a sale—is the cut of the film that most fans were first introduced to. It’s the version of the film I saw as a ghosts and goblins obsessed teenager, surely not alone in my predilection towards any VHS clamshell that featured the words “zombie” or “living dead.”

But Franco’s original title was more poetic, La nuit des étoiles filantes (or The Night of the Shooting Stars). Franco’s preferred version of the film, the one that most closely resembles his original script (what we now call the director’s cut), can be found on the Redemption Films video release from 2013, but it’s confusingly ascribed the Christina, Princess of Eroticism title (as film historian Nathaniel Thompson puts it, “close enough”). On his commentary track for Redemption’s Blu-ray release of the film, film critic Tim Lucas notes that “a shooting star is a dying star, which may have some relevance to the inspiration behind this macabre and lyrical movie.” That “dying star” was the late Soledad Miranda, a bright, young actress and early creative muse for director Jess Franco, who died in a tragic automobile accident at the age of 27.

“Each line, each shot is 100% pure Franco.”

— Alain Petit, writer/actor/collaborator

Redemption’s newly edited, definitive version of the film, includes a Christina, Princess of Eroticism title card and runs 79 minutes. It does not include either the Alice Arno garden orgy or the zombie footage shot by Rollin that gave the film its most infamous title. This version is more ambiguous regarding Christina’s journey to her ancestral home—is her family acting strangely because they are undead, or is Christina herself half-dead, intruding on a space between life and death? The film purposely plays with space and time, with Franco himself describing its style as “out of reality,” not consigned to moving from A to B to C in its plotting. And for that reason he calls it a personal favorite from this period of his career.

Shortly after completing The Devil Came from Akasava with Jess Franco, Soledad Miranda and her husband were involved in an automobile accident with a small truck on August 18, 1970, on a road in Lisbon, Portugal. Miranda’s husband survived, but she suffered fatal head and back injuries. She died at the Hospital of San José in Lisbon several hours later. A Virgin Among the Living Dead was not the first film Franco made after the untimely death of Soledad Miranda, but it is the one that feels the most haunted by it. It was also the first film he shot completely in Portugal, a still grief-stricken return to the site of her passing; not her home country, that would be Spain, but the location where her body and soul were disconnected, where Franco likely found her powers of the spirit the strongest. Portugal would become a common shooting location for much of the rest of Franco’s career. One imagines part of the reason, beyond its obvious architectural and seaside beauty, is because of its connection with Soledad.

“I shall be glad as long as I live that even in that moment of final dissolution, there was in the face a look of peace, such as I never could have imagined might have rested there.”

— Bram Stoker, Dracula

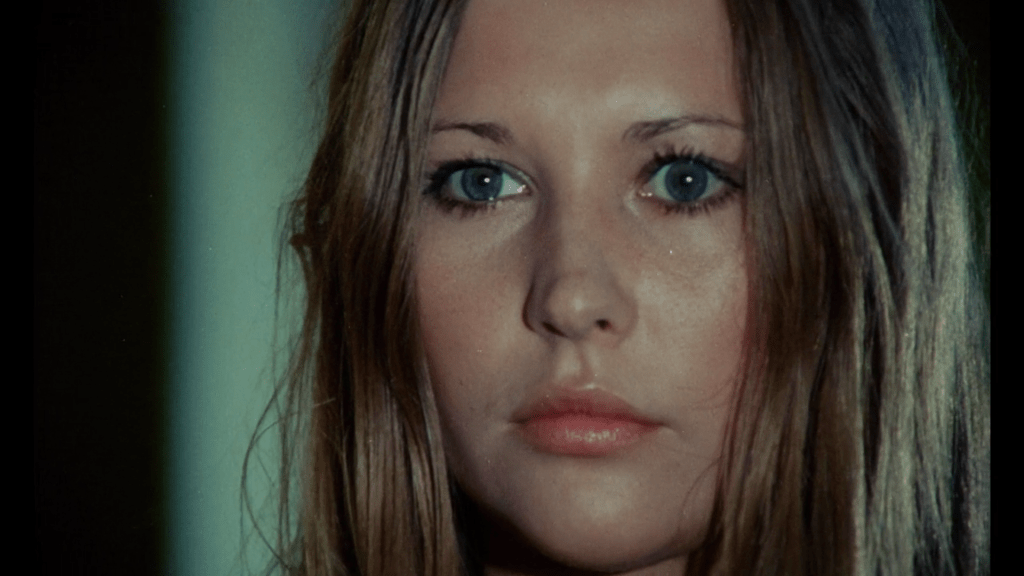

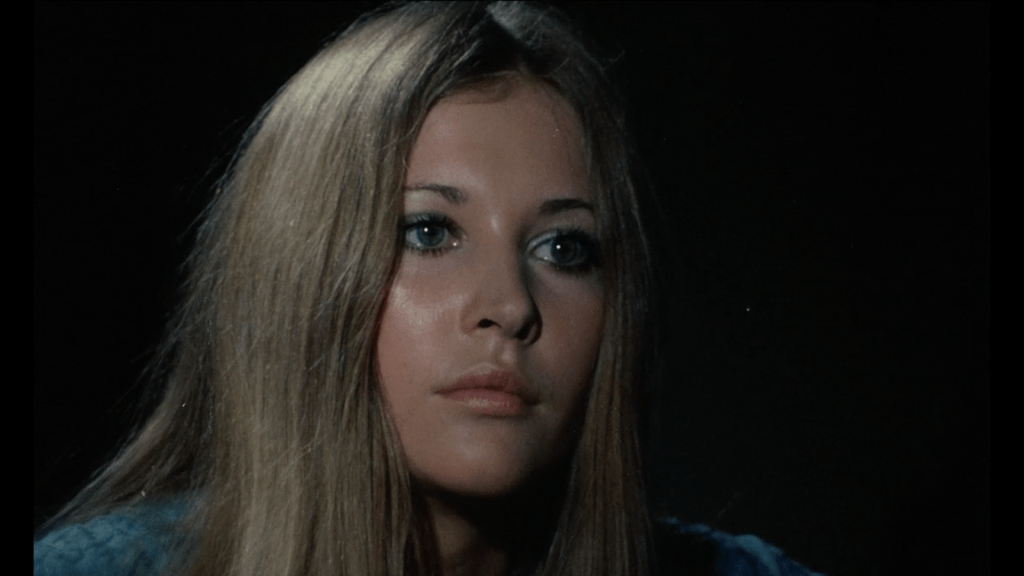

A Virgin of the Living Dead begins on one of these Lisbon roads, as our flesh-and-blood protagonist Christina has been summoned to her family’s estate, Monserrate, a real palace located in the Sintra region of Portugal. She is chauffeured by Franco himself, playing one of his many mute servant roles. Upon her death, Miranda was on her way to West Germany to sign a new, lucrative contract with Franco and producer Artur Brauner. In the film, Christina is on her way to unlocking the promise of a vast inheritance. In a further blurring of fact and fiction, several important characters in the film use their real names: Christina von Blanc is Christina Benson; Howard Vernon is Uncle Howard; and Carmen Yazalde (often billed as Britt Nichols) is cousin/prostitute Carmencé.

An incredibly prolific filmmaker, Jess Franco’s career is best understood when viewed through different eras, each punctuated by a working relationship with a different production company. A Virgin of the Living Dead was made just after Franco had ended his fertile, collaborative period with producer Harry Alan Towers. During Franco’s “Towers Era,” he made some of his biggest budget films, with well-known actors such as Christopher Lee, Klaus Kinski, George Sanders and Jack Palance. While his films under the tutelage of Towers certainly had a Franco touch, they were limited by the large scale and scope. Franco was a rare director that worked better with a limited budget, when left to his own devices, and evidence points to him shooting A Virgin of the Living Dead on the sly with leftover funds from a prior film. But even Franco’s most personal films had to be sold; they had to make money, and for a long time, and still today, A Virgin of the Living Dead is a hard sell.

“A rumination on the effects of depression.”

— Tim Lucas, film critic

At its core, A Virgin Among the Living Dead is more vampiric than ghoulish, but it’s still hard to categorize, and thus, difficult to market. It is influenced by Dracula (a mostly book accurate version of which Franco had just completed shooting), but in its director’s cut form, its closest companion is more Carl Theodor Dreyer’s somnambulistic Vampyr, with Christina acting as the Allan Gray character, moving through a dreamscape with little control over the horrific and sad circumstances happening around her. Franco expert Stephen Thrower describes it as “a cinematic poem; it’s certainly not a narrative.” Writer Richard Whittaker called it “a surrealist meditation on crippling grief,” and that descriptor, “surrealist” is important in understanding the film.

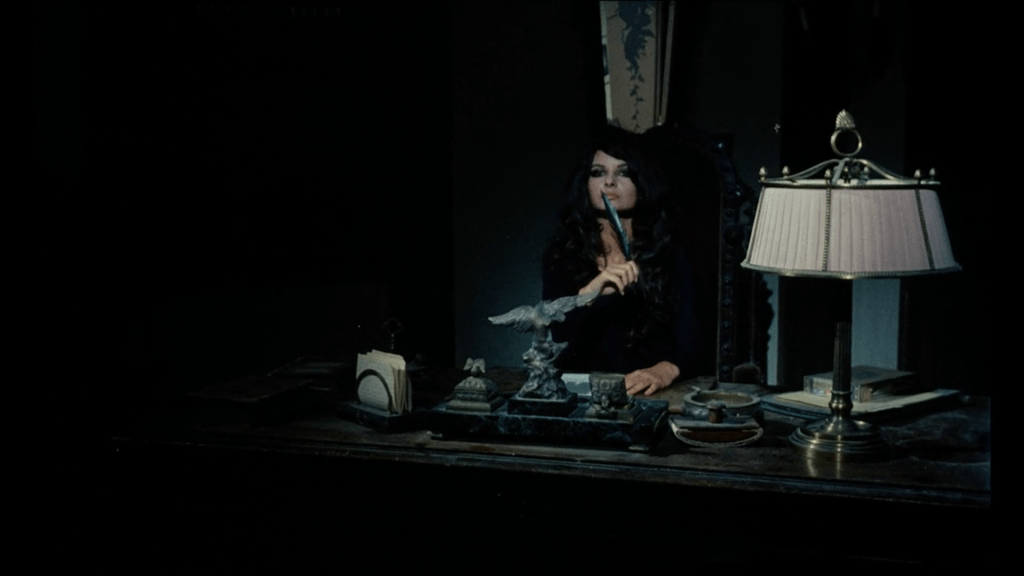

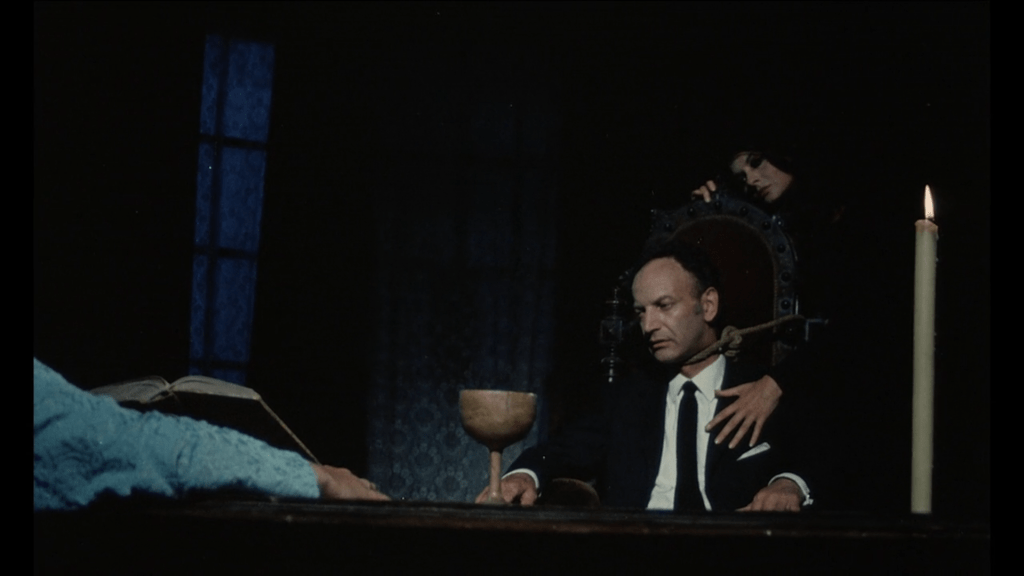

Tim Lucas, in his admirable attempt to make sense of such surreality, has an interesting interpretation of the film. His view is that Christina is a patient under observation at a psychiatric hospital. The inn at the beginning of the film is not an inn at all, and the white coated woman scribbling notes at a table (played by Franco’s then-wife, Nicole Guettard) is not a concierge, but the head nurse. And in fact, Lucas would argue that most, if not all, of the characters we see at Monserrate are employees, in some form or other, of the mental health facility.

I think I hear angels in my ears

Like marbles being thrown against a mirror

— John Darnielle, “Wild Sage”

Lucas notes that for as obtuse as the film can be, there is a “consistent pattern of symbols.” He believes Christina had a mental break after her father’s hanging suicide and was subsequently institutionalized. Much of what we see in the film are her paranoid visions and nightmares while under observation. In one infamous scene, Franco’s mute minion threatens her with the severed head of a chicken. On its surface, it appears to be just another strange vignette, intended to throw the viewer off-balance and have them laughing or scratching their own head. But viewed through a surrealistic lens, Lucas interprets this as a literal “cock” being waved in the virginal face of Christina. Throughout the film, Christina attempts to reject all manner of phallic temptations, be they physical totems, like the ebony dildo left in her room, hypodermic needles and thermometers, or the aggressive mauling by the inhabitants of the palace. To reject these symbols is to reject life itself, and soon death comes more forcefully.

So, we return to my glib opening remarks—why is this my favorite film? It’s honestly hard for me to say. I love its black humor, and its mix of the surreal and the grotesque. I find Paul Müller’s performance (one of many he would play as a disturbed or haunted father figure) to be one of his strongest, a sad specter that is reaching out from beyond the grave. I adore Bruno Nicolai’s ghostly score which is heightened by Edda Dell’Orso’s breathless vocals. Nicolai’s cue for one of the film’s most beautiful scenes—Christina’s father gliding through a glade, a noose around his neck—Lucas compares to “the chime of a finger tracing the rim of a wine glass.” Stephen Thrower accurately calls it “a mesmerizing vision that stands here as the apex of Franco’s imagery.”

It may all end tomorrow

Or it could go on forever

In which case I’m doomed

— Morrissey, “Piccadilly Palare”

The film itself is a warning against lingering on morbidity; an exorcism of depression. It’s a treatise on moving on from sadness (and in Franco’s particular case, from Soledad Miranda), while also respecting the dark and painful memories that make us who we are. A haunting doesn’t have to be a terrible thing, but when it goes on forever, it can be.

“Destiny has been fulfilled. We who share the same blood have been reunited. It is not death that has conquered life, but life that leads always to death. We will return forever to the banks of the River Styx…wandering in the tide without ever reaching the other shore. May destiny be fulfilled.”

The Blu-ray edition of A Virgin Among the Living Dead appears to be out of print. You may be able to still purchase directly from Salvation Films. The DVD is still available from Kino Lorber.