“How proud I am that you will do anything to humiliate me! You degrade me as deep as a man can degrade a woman…”

—Lulu, Earth Spirit/Pandora’s Box

“I’m not a slut, but I may become one.”

—Ewa Pobratynska, The Story of Sin

Bram Dijkstra’s Idols of Perversity brought to sumptuous life. You could write a thesis on the use of fin-de-siecle artwork used in Walerian Borowczyk‘s textured, decadent, erotic opus, or you could just read that painstakingly researched tome, which makes the case that much of that era’s art was part of a “cultural war on women,” a response to their progress and evolution in a new, modern world. Those beautiful Victorian images of recumbent, naked women? Dijkstra’s central argument is that they were actually part of a broader “iconography of misogyny.”

Ella Ferris Pell’s “Salome” / Charles Chaplin’s “Portrait of a Lady”

You’ll find art very similar to that which is featured in Dijkstra’s book intentionally scattered throughout Borowczyk’s Polish-filmed period drama, The Story of Sin. Not just in art galleries, but in households, cafes, market stalls, flophouses and bordellos (the latter also featuring pin-ups of French dancer and scandal magnet, Cléo de Mérode). And most striking, you’ll find that art reflected in the film’s final shot—our fallen heroine Ewa (Grażyna Długołęcka) lying supine in ecstatic death, breasts exposed, is like a recreation of one of the many images of “collapsing women” hung on salon walls throughout Europe.

“After the Masked Ball, ” oil on canvas by Charles Chaplin

It’s in turn of the century Poland where ingénue Ewa finds herself trying her best to remain pure in the eyes of her Church, but tempted by a handsome, almost-divorced lodger who showers her with attention, and offers glimpses of a wide world outside Warsaw. She tries her best to be the household nun that her society demands, but ends up the feminine evil they pretend to detest (but love to play with). Her downfall is her utmost devotion to Lukasz, that l’amour fou, offering up her own body and soul to him like she would her God. But then, as now, women of a certain faith are often told that Man is closer to the Almighty than their weaker-sexed selves, so why would we expect her to do anything different?

Images of vamps adorn the walls of Ewa’s bordello room

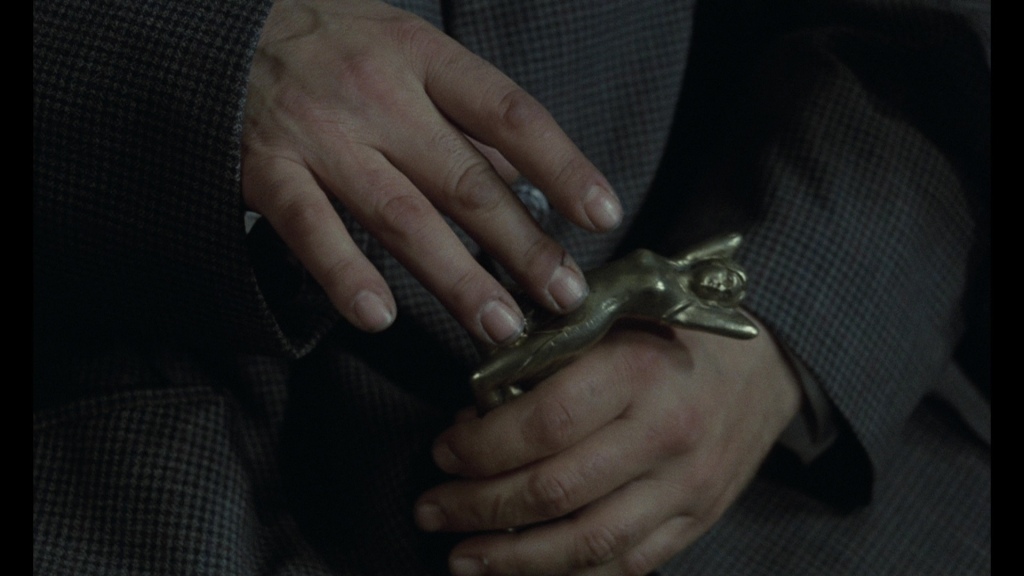

The camera swirls, hides, and often takes on first person POV. It gives the viewer the feeling of looking in on something forbidden, like watching Ewa (pronounced like Eve) devour that illicit fruit in real time (and sometimes, very literally, through omniscient binoculars). The visuals can be best described as richly detailed, every room and costume seems almost effortlessly accurate and period-specific (Borowczyk “tried to make the actors subordinate to the elements of the set design,” according to actress Grazyna Dlugolecka). But the design never takes away from the story, instead it enhances it, gives it a lived in feel, from the mirrors to the cabinets, no object is inconsequential in the Borowczyk universe.

That central plot of The Story of Sin is in many ways a 70s-liberated update on the age-old “fallen woman” films that had their peak in the pre-code 1930s, but can be seen even further back in the vampish silents, from Theda Bara in Salome or Greta Garbo as The Temptress. Dijkstra describes the turn-of-the-century vamp as such:

“By 1900 the vampire had come to represent woman as the personification of everything negative that linked sex, ownership and money. She symbolizes the sterile hunger for seed of the brainless, instinctually polyandrous—even if still virginal—child-woman.”

And while it can be argued that Ewa’s final form is that of the stereotypical female vampire, luring men off the streets, one gets the feeling that for her it’s a put-upon act, her heart’s just not in it. And in the end she sheds the role without hesitation for one last act of self-sacrifice in the name of mad love.

Greta Garbo in The Temptress / Theda Bara in Salome

Ewa as vamp is a brief, final-act turn; for much of the film the most obvious influence is Frank Wedekind’s “Lulu Plays,” made most famous by the G.W. Pabst film Pandora’s Box starring Louise Brooks (a play that Borowczyk himself would adapt more faithfully in his 1980 film, Lulu): innocent/pious woman is led to love and ruin, sometimes she finds redemption in the end (through her suffering and sacrifice), more often she is punished for her transgressions. But Borowczyk gives his cautionary tale a political bite, with crooked counts and an entire system set against female advancement. How different would this story be if Ewa’s beloved Lukasz was given the quick divorce he sought, instead of having to travel from country to country to find a sympathetic court to grant him one?

Louise Brooks in Pandora’s Box / Grażyna Długołęcka in The Story of Sin

Of course, the message is open to interpretation. In a recent interview, Dlugolecka tells the story of a priest visiting her mother’s home after Christmas. Fully prepared to bed for absolution for starring in such a wicked picture, the priest surprised her by revealing he had shown the film to his theological seminary students, as it proved a powerful point about the “entity of sin.”

The Catholic priest’s warning to Ewa at the beginning of the film to “look not at obscene paintings” was maybe lost on the young seminarians, as the film is like one, long, sensual piece of erotic art. It’s a visual manifestation of the film’s many longing letters set upon the breast (“It’s not a letter, it’s a kiss!”), and the rose petals pressed on naked skin. A testament to Borowczyk’s skill that he’s able to create something that feels much more explicit than it actually is. Decadent, sad, beautiful, it’s a masterpiece of woman’s unending failure, in the eyes of the world, to make thy soul as beautiful as thy flesh.

“She’s tired of your moral tales.”