“Father…I feel sick without you.”

After the release of his debut film, The Perfume of the Lady in Black, director Francesco Barilli went silent. He had projects in mind but they never came to fruition. In an interview for the blu-ray release of that film, Barilli talked extensively about his career. It’s obvious that he had trouble working within the parameters of the studio system (“I’m a capricious director, for better or worse”). He was cocky, and not keen to take suggestion. The project that would eventually become Hotel Fear apparently came to him from a producer who thought the story would fit Barilli’s style. And it does, but it also feels dirtier, closer to the nastier side of women-in-peril exploitation cinema than the bright colors and often humorous tone of early giallo. There are no jokes here. No bumbling detectives. No escape from a very specific hell on earth.

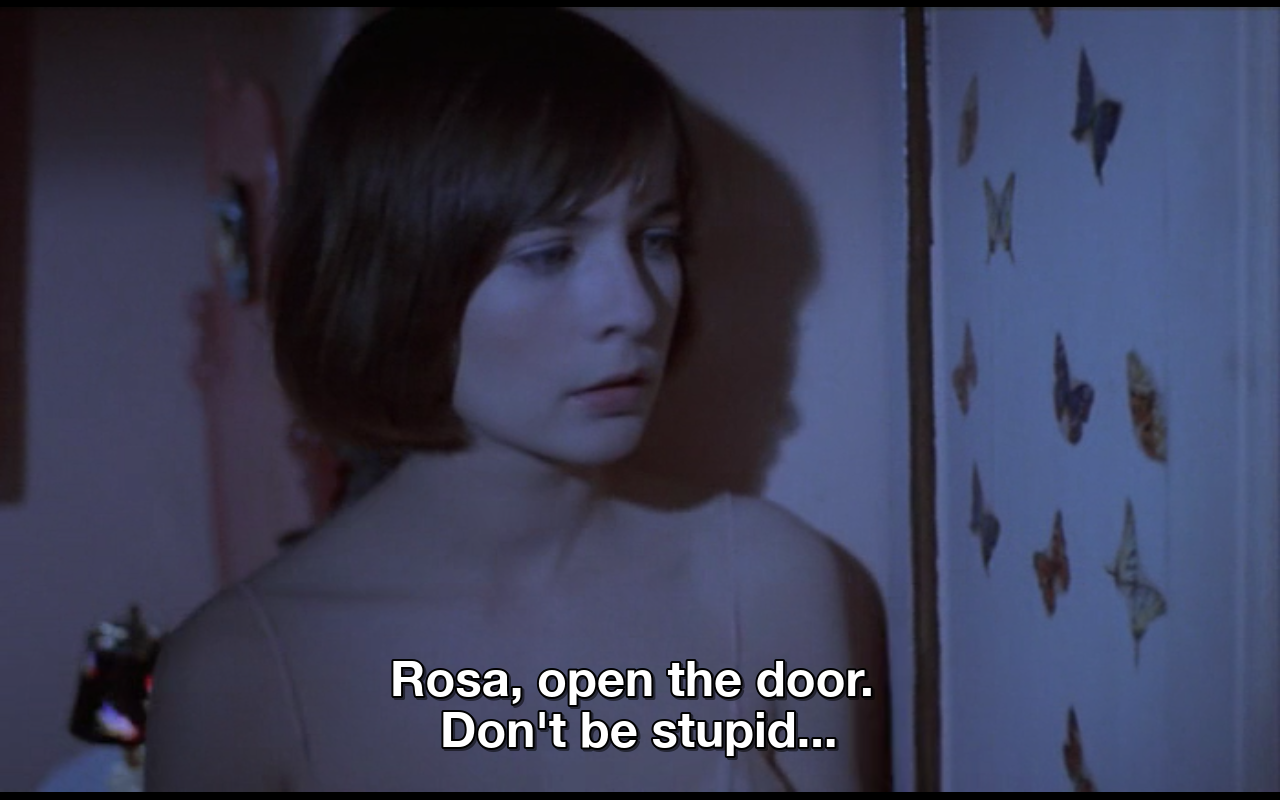

It has the trappings of a giallo in tone, style, and mystery— but more than that, it’s a war drama, and an early example of a rape revenge film. Hotel Fear is hard to pin down. Rosa (Leonora Fani) is a young girl waiting for her father, a World War 2 pilot, to return home from the war. She works at a run-down hotel with her mother, the guest ledger filled with burnouts, castaways and cutouts: gross men who grab Rosa’s waist and whisper their dreams in her ear, a touchy Lothario with a pencil mustache (Luc Merenda), and women who encourage them. As bombers fly overhead and the lights go out, bad things begin to happen in the dark.

Rosa’s mother Marta has a lover hidden in the attic who has apparently deserted the war. This is where things get messy. In the Spanish version of the film (The Rape of Miss Julia), the man is her MIA father. In the Italian version he’s just a cowardly deserter. When her mother dies mysteriously, Rosa is bombarded by suiters looking to bed her under the guise of protection. Even the young local boy who brings her food from his uncle’s shop seems to expect something in return. A pair of mysterious men show up, demanding a room. There are hidden diamonds, unsatisfied wives, and a suffocating feeling that things are about to blow.

“War is a bad thing for hotels,” Marta says, but it’s also a bad thing for defenseless women in war torn Italy. Dour stuff to be sure, but there is some hope knowing the war will soon be over. Or maybe like in Guy Maddin’s Archangel, it already is, but these ghostly guests haven’t been informed yet. Our fathers may not return, but we’ve learned to live without them. At the very least, that’s something.